The Loneliness of the Long Distance Leader

julian burton

You may have a bold vision of the best way forward - but does your team share it?

Will they follow you?

Use the form on the right to contact us.

You can edit the text in this area, and change where the contact form on the right submits to, by entering edit mode using the modes on the bottom right.

11-13 Weston Street

London, SE1 3ER

United Kingdom

020 7199 7099

Supporting organisations to bridge the gap between strategy and action at moments of change, making sense and shaping conversations with Big Pictures.

Filtering by Category: Leadership

You may have a bold vision of the best way forward - but does your team share it?

Will they follow you?

When an organisation is going through a potentially uncertain period of change there can be a tendency for a distance to arise between leadership and staff. Decision-making in such volatile environments can be fraught with disagreements and ambiguities, with leaders finding themselves debating more and more on which course of action to take. Sometimes there is just too much input to consider and the temptation is to limit the options and control the situation.

From the point of view of those not sitting in the decision-making circle it can feel difficult to influence or even be heard by the top table - leading to widespread frustration. A communication void further exacerbates the situation, with people filling it with rumour and speculation about what is going on “up there”.

The onus is on the leadership to be aware of this dynamic in times of uncertainty and do what it can to include, involve and listen to employees’ concerns and perspectives. Getting a broader viewpoint on a problem is rarely a bad thing and often the solution lies with those who do the work.

Have you come across a HiPPO in a recent meeting? This acronym stands for ‘The Highest Paid Person’s Opinion’. This refers to the impact of rank or hierarchy in a meeting where people will often fall silent, deferring, for various reasons, to the opinion of the person with the most power and highest salary.

HiPPOs can get in the way of good decision-making. Having a HiPPO in the room can dominate a meeting as it often carries a lot more weight than other voices. People may feel too scared to challenge a dominant opinion, even though they may fundamentally disagree with it, while others may pay lip service and be eager to please and toe the line. The owner of the dominant voice runs the risk of believing they alone have the best ideas and miss the opportunity of hearing the valuable insights or ideas that come from different voices in the room. A leader may be aware of the impact they have on others but it’s not easy to create a culture where people feel its safe to question a HiPPO without fear of reprisal.

The interesting thing for me is that HiPPOs only exist because of the relationships in the room, with everyone in a sort of collusion in keeping them present. It seems to me that it is vitally important for everyone to be aware of the impact they have on others and how one reacts in silencing oneself in these dynamics.

Taking ownership of the parts we play in creating HiPPOs is the only way to stop them turning into elephants.

Was there a HiPPO in the room today? What was the part you played in keeping it alive?

We like to believe we’re collaborative - yet it’s all too easy to lose sight of other people you should be having more collaborative relationships with. Do you know how they feel about it? Are you really listening to your people?

Power relationships can make it almost impossible to speak up to someone in charge. As a leader, if you’re not hearing feedback then you're missing an opportunity to learn and demonstrate the new behaviours you want to see in the culture. Just by saying you’re going to be collaborative doesn’t mean you will be, and there may be no one with the courage to hold you accountable. How collaborative do those working around you really think you are?

We often hear leaders’ frustration that the frontline don’t get the new strategy. And we hear from those people that they are being asked to implement a new change strategy they don’t understand, don’t feel connected to, or don’t believe in.

However brilliant a strategy looks in Powerpoint, it may not be worth much if it’s created at the top and cascaded down onto the people who will be delivering it. The one-way nature of traditional "comms" can create alienation, confusion and lack of meaning if it doesn't encourage the dialogue necessary for people to make sense of and fully understand the changes being asked of them.

This separation between strategy development and its implementation is often cited as a major cause of failed change programmes. The frontline should be involved in the strategy development process. Listening to what they have to say and taking their ideas, concerns and objections seriously can go a long way to creating a genuinely shared narrative that everyone can feel part of and committed to.

In organisations with a ‘command and control’ culture there is the expectation that orders should be followed to achieve a desired result – rather like following the instructions from a sat nav to reach a destination. This may usually work well, but learning is limited, and the dependency on the sat nav can leave the driver lost or stuck if anything goes wrong with it.

In organisations where individuals are trusted to take more responsibility for their work people have an incentive to take more care, and can become more invested in their outcomes. They are reading the map and charting the route, and having to be alert to their surroundings. Things will go wrong from time to time, but then lessons can be learnt and better solutions found. Sometimes taking a new turning will lead to discoveries and opportunities that would never have appeared on the sat nav.

The well-worn tale of the Apollo Program, the visiting president, and the helpful janitor serves as a memorable illustration of team engagement and an apocryphal narrative about storytelling. After all these years it still stands out as a great example of the motivating effect of an inspiring vision.

“We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organise and measure the best of our energies and skills.” John F Kennedy, 1962

Stories invite us to go on a journey and are so effective at delivering a message because they give the audience a way of engaging with the details and caring about the outcome. We are drawn in by being able to relate to the characters, their motivations and needs. We also recognise the challenge in the current state and become curious about how it can be resolved. The challenge may demand a journey or quest, which we hope will have a fitting outcome.

Every organisation has it’s own narrative and while not all projects and stories can be as uplifting or as clear-cut as a mission to the moon, seeing our place in a bigger picture can invest work with more significance and be emotionally compelling. Having the opportunity to reflect upon a narrative and make sense of our role within it allows us to consider new possibilities, inspire us to take on new responsibilities and conduct our daily work mindful of a long-term strategic vision.

Most of all it helps us take ownership of the challenge and consider what we can do differently to help overcome it. The scale and status of one’s role does not necessarily define the value of each contribution.

Even though we may have little influence in the grander scheme of things, by taking personal responsibility to manage the quality of our work we can maximise the positive effect we have. And if everyone has this same personal investment in the outcome of the story there’s no limit to what can be achieved.

Transformation programmes can be challenging and disruptive, especially when staff are expected to get on with their business as usual efficiently throughout. Hunkering down to try to focus on what they need to get done, with a dull ache of change fatigue, they’re not at their most receptive.

To break out of this defensive position people must feel that they are actively involved in a programme, not merely on the receiving end of the latest salvo from the leadership. A chance to be listened to, to contribute, to influence. That the issues they have experienced personally can be recognised more widely, and addressed. In that way they can become active participants, playing a part in driving a change rather than just being observing passengers.

Without this meaningful involvement a transformation programme risks being hobbled from the start - regarded by employees as the latest attack on the order they’d carefully established, and something to be resisted or quietly subverted.

It should be an opportunity to embrace, as the route to changes that could make a positive difference for them and their organisation. One way or the other they will find a role to play: it all depends on whether the transformation is done with them, or to them.

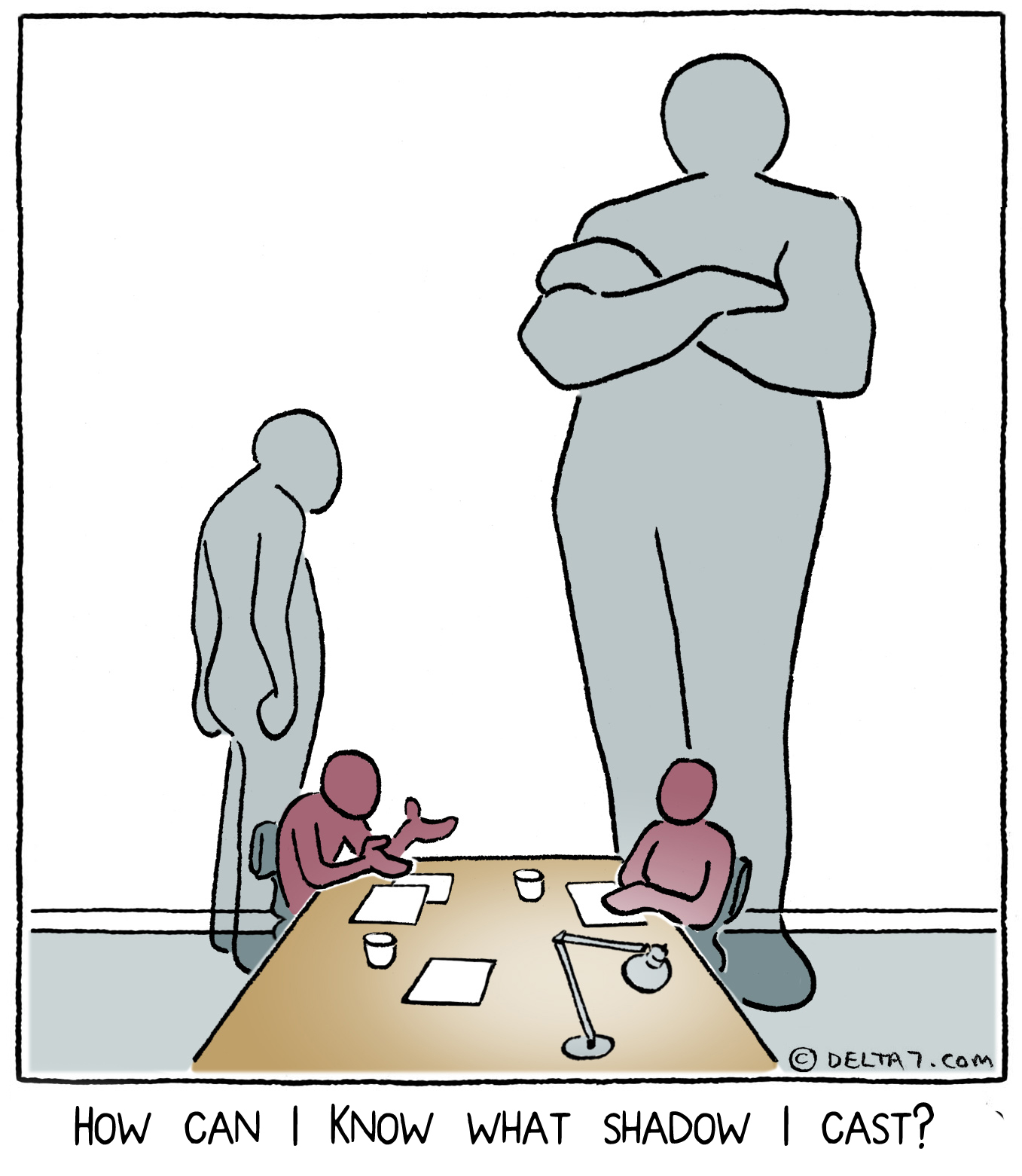

For me my shadow side is the parts of me I can’t see or I’m completely unconscious of that drive my behaviours and has a significant impact on the quality of my relationships. Have you been in a meeting recently and felt disempowered by someone who has dominated the conversation so much that there was no space for anyone else’s views? Or it felt too risky to share your thoughts, let alone give them feedback on their impact on you?

I’ve only learnt recently that sometimes my silence in a meeting can shut others down more often than my voice does! Since getting that gift of feedback I’ve become more sensitive to what happens in the interactions that I'm taking a part in. And I've become more curious about how I show up, and now want to learn more about the parts of my shadow that closes down others' voices and contributions.

Given that I can’t normally see my own behaviours, I really need others to give me honest feedback on what they see and the impact they have. The trouble is there can often be different realities existing simultaneously in a meeting; what I think I’m doing and how I like to think I’m showing up, and how others see me behaving. It can be obvious to other people how I’m behaving, yet hard or impossible for them to give me feedback if they don’t trust me or it doesn’t feel safe enough.

This is a real bind for me, as how can I learn to develop my self-awareness if it’s not safe enough for others to speak up and give me feedback on my behaviour? If I don’t know what impact I’m having I can’t learn to change my behaviours - to the ones that could create the relationships of trust needed for it to be safe enough for people to give me feedback in the first place! AARRGHH!

Moving on from my frustrations, I’ve been getting a sense that I need to work on learning to listen more deeply and actively, from a calmer place, responding differently from this position and noticing what happens. If the quality of trust shifts, I hope to get more feedback that can shine some light onto to the parts of my shadow that seem to close down others and get in the way of more open and honest conversations.

A key point of discretionary effort is that by definition it is discretionary. As a leader you can't demand it - you have to earn it. As soon as you set it as a goal you are essentially expecting people to work for free.

According to Engage for Success "Employee engagement cannot be achieved by a mechanistic approach which tries to extract discretionary effort by manipulating employees’ commitment and emotions. Employees see through such attempts very quickly and can become cynical and disillusioned."

The question becomes why do people sometimes choose to give more of themselves than is asked for in their job description? It is about care and the relationship they have with the people they work for and work with.

From a management perspective it is clear that the challenges in the world are requiring organisations to respond in a different way; that managers can't succeed without employee discretionary effort. The danger is that as soon as you identify discretionary effort as essential you have to consider what the implications of this are when heard by employees.

The answer is care and relationships. How we take care of each other, how we relate to those people who we spend more time with than our own families will always impact the level of commitment and care you will receive back. This can be the only motivation - otherwise the care becomes false and people will see through that very quickly.

The most amazing example of discretionary effort I have witnessed is within our wonderful (and under cared for) National Health Service. Staff choosing not to go home until they can find a bed for their patients. Preparing food and drinks for them and caring for them in ways that are not asked for or expected. And the reason they do this? Their conscience won't let them do anything else. With the challenges of resourcing and capacity issues facing the NHS it is this quality of care that keeps it functioning.

My experience

When I first became a manager I was young - a lot younger than some of those I was managing. I had a steep learning curve ahead of me and I failed - a lot - until I realised that I had to earn their respect, trust and care. I tried often to short circuit the process; find a quick way to get people to follow me, manipulate them, guilt them into staying later. I always thanked them for their effort, but that really wasn't enough.

I remember one phrase I used a lot when I was talking about work was 'They don't need to like me. I don't need friends, I need employees that do their job.' I was honestly kidding myself. This was my defence when I had to be tough, but what I realised was that actually they did have to like me and I had to like them, but more than that: we had to care for each other. This was the first time we functioned well as a team, we had each other's backs and we did what needed to be done for each other. I stopped having to think about asking for more because we all gave more where we could and they saw me doing it as well. We were in it together and that's what made it work. My new phrase when I thought about work was 'don't ask others to do something you aren't prepared to do yourself.'

The biggest challenge today for many leaders involves dealing with very complex, systemic problems and what can feel like impossible dilemmas. It can feel overwhelming trying to balance multiple stakeholder groups, financial pressures, demand for quality improvement, the wrath of senior leaders, raising safety standards and conflicting values, all at the same time. In short, they are confronted with what leadership professor Keith Grint calls a “wicked problem.” These are problems that are messy, have no one solution, occur when there is increasing uncertainty and a pressing need for wider collaboration.

Systemic wicked problems go beyond the capacity of any one person to understand and respond to, and there is often disagreement about the causes of the problems and the best way to tackle them. Wicked problems are also difficult to tackle effectively using traditional thinking i.e. that the best way to solve a problem is to follow an orderly and linear process, working from problem to solution. Resolving wicked problems requires changing the way we think, balancing overly rational approaches, using innovative ways of team working, trying new behaviours, time to step back from the chaos for richer sense-making and more authentic conversations.

To think systemically, beyond our local situation, we all need imagination to understand the other parts and connections of the wider system that we don’t experience directly, that we may have an impact on and yet may be out of our control.

When lots of factors need to be considered in decision making, visualising the bigger picture, for example, how a local health system interacts with the wider systemic context, can help a leadership team explore how their decisions might impact different parts of the system. A team can then make sense of how things connect and see an overview that clearly shows the complex interrelationships that are difficult, if not impossible, to represent in words. Gathering a whole team's individual views into one big picture that represents a shared perspective in a way that can transcend personal differences and bring together their collective thinking.

As an example we recently we worked with an NHS trust exec board who were facing a wicked problem. As well as the business-as-usual agenda items, and the pressure to deliver their new strategy, it was critical that they found a more creative way to explore the different dimensions of a new strategic partnership with two other trusts. This involved exploring new organisational forms and to deliver new models of care. Their awaydays often felt hectic and had many tacitical agenda items to cover. The trust’s OD Director wanted to shift the conversation about difficult strategic decisions and be more systemic in their thinking.

The challenge

”Our fundamental challenge was how to look after our own trust and considering our own community needs, while at the same time looking at what is best for the wider patient care system. We need to be answerable to local communities and at same time need to make strategic decisions for whole health system.” ...“The sort of questions the Executive board were asking themselves were: What new organisational form will enable us to deliver better healthcare? How can we deliver systemic change that improves the quality of patient care and reduces costs at the same time?” Trust O.D. director

The OD director brought us in to support her to change the conversation with her board using our Visual Dialogue methodology. A Visual Dialogue is a facilitated conversation that can support leadership teams to have better quality meetings when they are struggling to make sense of complex problems. The conversation was facilitated to focus on their big picture of the “wicked problem” which was created out a a series of 1:1 interviews. We listened carefully to what they said and encouraged them to speak from a personal perspective.

The picture helped to shift the way the team discussed their challenges by showing the complex interdependencies and relationships between critical factors and how they affect each other to. The facilitator kept the group's attention focused on the picture and what’s most important and created a safe space to test the level of consensus on critical issues. The session encouraged the team to think and talk more creatively, systemically and long-term, beyond their personal situations and agendas.

The Big Picture of the board’s wicked problem

What happened?

“Our board members often have their own bit of the system to sort out and prefer to break complex problems down into the smaller parts that they are more comfortable with, that are within their comfort zone. Though that might only result in one piece of the system working well."

"The Visual Dialogue session shifted the quality of the conversation and using the picture encouraged them to think more systemically about local issues the process changed the level of questions they were asking, and so challenged their thinking to a new level."

"It enabled the board to think and talk more systemically, beyond their own personal points of view and level of thinking, about wider issues and how these impact each other."

"It created space for the board to test their level of consensus on partnerships, and go beyond personal values to consider the greater good. They could explore the ethical dilemmas involved and get beneath the commercial and transactional focus of their role, down to a transformational one where they were getting an idea about if they had shared values and talking about values based leadership. Ultimately the session was as much about about building relationships and uncovering personal values as it was about solving operational issues."

"The quality of the conversation was more strategic, fluid and creative, it stopped them getting into detail too quickly. The Big Picture kept the conversations from getting too operational, too quickly, and forced broader thinking, it kept them strategic. It stopped them deconstructing the “problem” down to something they can control and manage."

"The big picture allowed me to keep them uncomfortable in a non-threatening way. It kept them in a place of looking at the interdependencies. The big picture showed most of the system, so the board could see they are facing an intractable problem, which can’t be solved with an action plan, and there is no commercial solution currently. So it encouraged them taking a broader view while keeping it personal - bringing alive the things they have to consider and deliver on."

"The Big Picture was like an interdependence map - you can’t look at one isolated element without seeing connections and consequences. Everything is there in the picture - it showed the complexities of the environment in one place - which papers can’t do. And it helped in understanding the complexity in a way they couldn’t have done reading board papers. It stimulated thinking about potential consequences out side of our normal boundaries as it can be difficult to move out of your own familiar lens/way of understand the world. The conversation raises consciousness that you can’t take actions in isolation, it stops you thinking that you can acts on things alone. “ If you make a decision here- it makes you think- what’s the impact there”. It stopped disrupted their linear thinking by bringing to life all the complexities involved in running the trust."

"Having a picture made it easier for people to declare openly that they didn’t understand “that” [pointing at something specific in the picture]."

"The Visual Dialogue session allowed the board to challenge each other and opened up a different conversation and a different space to think in. The Big Picture didn’t provide answers, but it forced systemic thinking.”

julian@delta7.com, 07790 007 560

I was at an ODNE conversation this Monday and one subject that came up was about what self-organising meant. We reflected that it can be hard to get a grip on what this word means, let alone work out how to advise leaders how they can create its enabling conditions. I have an insatiable curiosity, so consulted the oracle; Wikipedia!

Self-organisation is a process where some form of overall order or coordination arises out of the local interactions between smaller component parts of an initially disordered system. The process of self-organisation can be spontaneous, and it is not necessarily controlled by any auxiliary agent outside of the system.

And the dictionary; the spontaneous appearance of orderly structure and coherent pattern.

So to apply these definitions to the conversation itself that we had that day, self-organisation meant that the relationships and conversations in that very room were organise themselves without any one person being in control, within reason. Within the simplest of liberating structures, the group decides what to do, when to do it and how, without any external direction. No one person dominates the group by closing down others' honest opinions. I don't think we had any conflict that day, but if there were any, I would hope that we would have courageously surfaced it as a source of diversity and not avoided it. And that is the really hard stuff.

Together, without planning, we enabled the sort of spontaneous and improvised conversation in which new, shared meaning was being created and relationships nurtured; i.e. organised coherently. I suggest that the new order, or gestalt that we created felt energising and motivating. We had co-created new, more coherent and satisfying patterns of experience, relationship and knowledge, all in the space of 3 hours!

So the learning for me is that, when I struggle to understand a highly abstract term such as self-organisation, I need to drop down into my felt experience and sense what are the qualities of conversation I'm living in. If I feel more alive and connected and inspired in that moment, its probably because others are feeling the same. And in the midst of our self-organising, we are typically not aware that we are, our attention being on the content of the conversation.

If you were at the same meeting as me, what did you experience? How does my description land with you? How could we learn together more about self-organisation in the next meeting?

BTW, this painting was first shown at the Art of Complexity exhibition at the LSE in 2003! Thanks Eve for hosting it x