What do you need to do your OD work? When we are faced with this question we often jump straight to a list. In this blog post we want to provoke you to think about the space you grant yourself to think, reflect and renew so you can be the best version of yourself within your OD work.

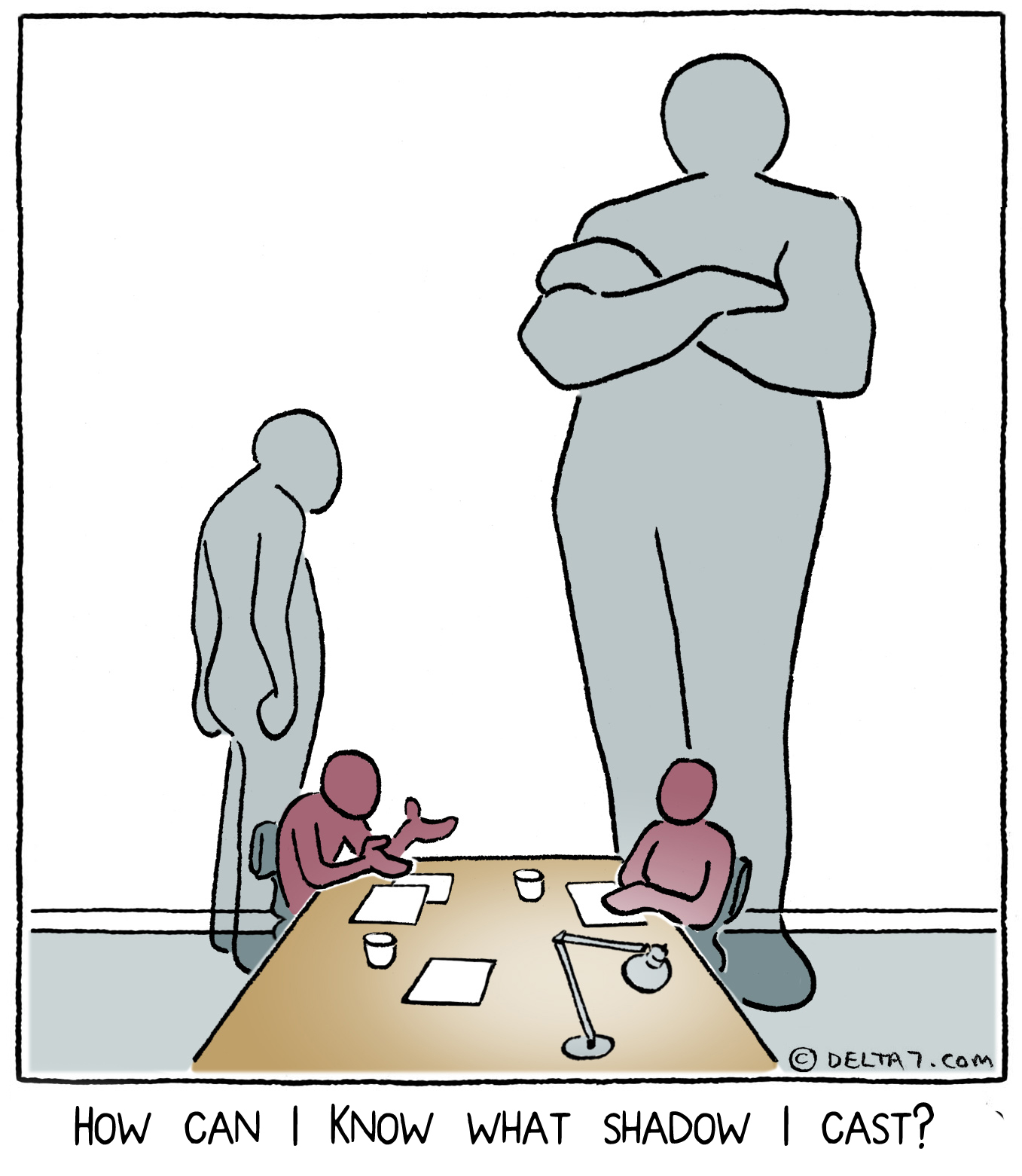

In OD we are often taught to think about the prevailing narratives, the ones taking centre stage, the ones which may be reflecting something important AND we are taught that part of our work is to help reflect back the reality of people’s experiences as they go about their lives. We are hearing two narratives, amongst others. A narrative about unsustainable workloads, of espoused values and behaviours which are not enacted in the workplace, but paid lip service to in reports and on office walls, of work intensity and a busyness created in part by the amount of 24-7 connection we now all experience in our lives.

And a second narrative spoken in a hushed voice that people crave spaces where they could just stop and breathe.

It was against or because of this backdrop of these two narratives, that a few of us in the field of OD decided to take ourselves away and create a different type of space. This space would be ours to create and manage, it would offer us the time to spend on things that were important to us and it would be a SLOW space.

The term ‘slow’ wasn’t a term we knew, it just sort of arrived and now I am frequently asked what a slow space actually is!

For those of us involved in the enquiry it was a space in which we could think, reflect, review and restore. Such a space is important because it nourishes our soul and for many of us our work is much more than paying the bills it is about our contribution to world, it is the work of our heart. So, with the prevailing narratives in mind, a colleague and I began to dream about going away to a place we could share time together around our work, think together, debate together and we liked the idea of creating an OD salon in the style of our European colleagues.

Very simply we found a retreat house, booked a couple of rooms and invited people to join us via Eventbrite. We saw ourselves as the hub of a self-organising group, everyone would organise themselves, no one would book rooms on behalf of others, there would not be an agenda. Whoever turned up would come with a warm heart and an open mind. In a roundabout way that is what happened and we also learned a lot!

We learned that even a self-organising group needs co-ordination, someone has to take the first step. Then there is a need to hold the boundary because we found people wanted to know what would we focus on? what would we do? These questions felt like an invitation to step into a leadership role. We learned that if you do not hold tight to the self-organising principle then others will look for a leader to lead. So, one message is beware the need for a leader and if you are a habitual leader you might want to practice some self-control and leave the leadership baton firmly on the floor.

As we talked of our up and coming salon on social media interest pick up in the strangest of manners. People started to ask “would we share our outcomes?”, I was quite clear that my outcome would be my outcome and I wouldn’t be taking the time to share it with anyone! I thought a lot about that, how do you share a full heart, a feeling of connection, and peacefulness deep inside? The social media interest sparked a really interesting realisation, people expected us to produce something because we were gathering. It really reinforced our view that we all need a space where we can talk, share and think without being asked about the return on our investment.

One important point to note is that that everyone was resourcing themselves to participate in the salon. Everyone believed that it was sufficiently important to commit their own time and money to the goals we sought. It might have been different if this had not been the case.

This was our time, a slow time, away from work but about the work of our heart’s.

Upon arrival deciding what to do with our time was a little strange, most of us were used to agendas, running from one meeting to another, eating whilst working and seldom stopping until the day was done. We gathered on a cold, late winter afternoon in a warm sitting room with coffee and cake and talked about what we might do with the next 24 hours. We shared why we had come to this slow space, what we were seeking, what we were focused on in our practice. This was a heartening experience, hearing of people’s interests, passion and requests to be heard and supported.

Gently and in a bounded way we navigated our way around planning how to use the first part of our time running up to supper. I personally owned my own discomfort at not knowing and not having any agenda. This response had taken me by surprise as from its inception we had planned not to have a plan! However, negotiating the use of time felt like such an important thing to do, working truly collaboratively it was a joy to listen, contribute and share. These slow conversations, in a physically welcoming space were what we had been longing for.

I have been asked ‘how important was the physical space?’, I think it was very important. We gathered here, a simple, spiritual, quiet space with a bar! We felt nurtured, the staff cared for us, the food was wholesome, simple and delicious. They cared that we had everything we needed. The bedrooms were simple, welcoming homely spaces, the gardens were inspiring, peaceful. As we closed for the night and made our way to rest we were treated to a spectacular display of stars from one of the least light polluted places in the UK. I have been asked could you have gone to a nice spa hotel … I personally don’t think so.

As we reengaged at breakfast I believe we were feeling the effect of the slow space, we lingered over food, and gathered to focus on the next 6 hours together. Once again, we collaboratively worked through what it was we wanted to focus on, it was a gentle enquiry. We shared resources, moments of reflection and enjoyed just being together. Our usual routine of evaluation, action planning and next steps fell away. It was liberating to stay until we wanted to finish, to follow our conversations and learn together and to restore our faith in our work, ourselves and each other.

Our process to create a slow space was a simple one:

Decide to gather

Select a slow venue

Put out an invitation to self-organise and attend

Gather and work through your feelings of being in a slow space, exploring what it means to be ‘off your grid’ for a while

Collaboratively debate and agree what it is you want to focus on the most (we learned that there will be far more than you could ever get through)

Hold back your usual patterns of outcomes, outputs and action plans

Notice your reactions to the slow space, it’s really important data!

I have been asked a number of questions after our gathering, which I will not repeat here, maybe they are for another posting. But the most important question “what was the best thing that happened at the Salon”

My response WE LISTENED TO EACH OTHER and how often does that happen each week?

Maxine Craig

Email - Twitter