Blog

Filtering by Category: Communication

The Top Table

Delta7 Change

When an organisation is going through a potentially uncertain period of change there can be a tendency for a distance to arise between leadership and staff. Decision-making in such volatile environments can be fraught with disagreements and ambiguities, with leaders finding themselves debating more and more on which course of action to take. Sometimes there is just too much input to consider and the temptation is to limit the options and control the situation.

From the point of view of those not sitting in the decision-making circle it can feel difficult to influence or even be heard by the top table - leading to widespread frustration. A communication void further exacerbates the situation, with people filling it with rumour and speculation about what is going on “up there”.

The onus is on the leadership to be aware of this dynamic in times of uncertainty and do what it can to include, involve and listen to employees’ concerns and perspectives. Getting a broader viewpoint on a problem is rarely a bad thing and often the solution lies with those who do the work.

Are you really listening?

julian burton

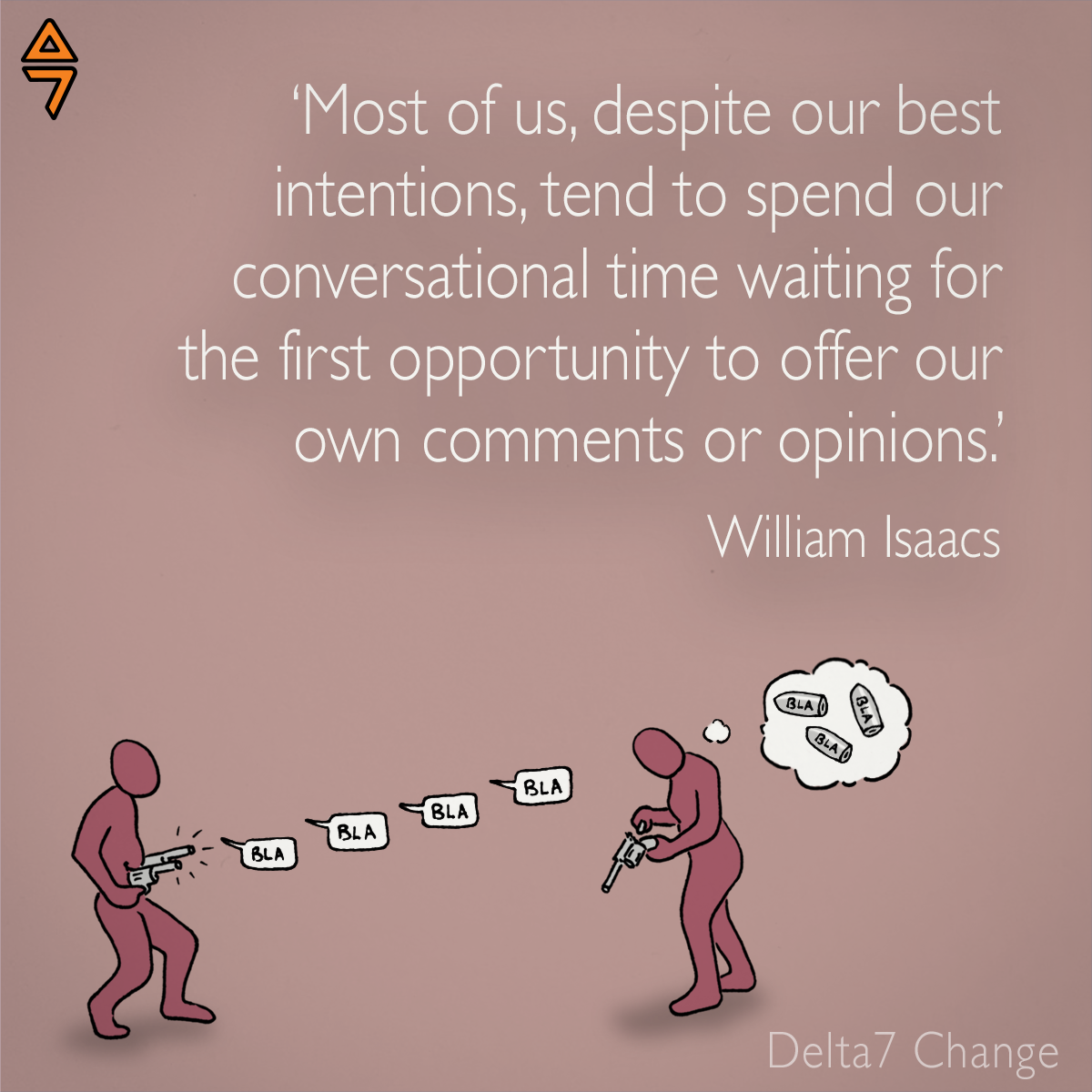

We believe change happens though conversations. Conversations require listening, which can lead to learning, mutual understanding and better relationships.

Hearing from different perspectives disrupts usual assumptions and encourages collaborative, creative thinking, which can lead to more considered solutions. Honest, candid dialogue can counter scepticism and resistance, building engagement and earning respect.

Listening requires being present, and it is all too easy to be distracted by background thoughts and considerations that may be running through our heads. Not least of these are issues concerning ego; that the direction of the conversation will be a reflection on our personal abilities, and therefore status. To demonstrate our abilities we want to make intelligent, ‘high value’ contributions, but it’s difficult to process lots of new information quickly so we tend to seize upon the things we can respond to confidently. If we try to anticipate where the conversation is going in order to prepare our response then we stop being curious - about the areas where we feel weak in order to capitalise on the parts where we feel strong. We can attempt to dominate the conversation so that there’s less new information to process and we can feel more in control, but by listening less we learn less.

Great conversations can be insightful and productive - and they require people to be curious and really listen to each other.

Why isn't our new strategy taking off?

julian burton

We often hear leaders’ frustration that the frontline don’t get the new strategy. And we hear from those people that they are being asked to implement a new change strategy they don’t understand, don’t feel connected to, or don’t believe in.

However brilliant a strategy looks in Powerpoint, it may not be worth much if it’s created at the top and cascaded down onto the people who will be delivering it. The one-way nature of traditional "comms" can create alienation, confusion and lack of meaning if it doesn't encourage the dialogue necessary for people to make sense of and fully understand the changes being asked of them.

This separation between strategy development and its implementation is often cited as a major cause of failed change programmes. The frontline should be involved in the strategy development process. Listening to what they have to say and taking their ideas, concerns and objections seriously can go a long way to creating a genuinely shared narrative that everyone can feel part of and committed to.

Going to the moon and back

Delta7 Change

The well-worn tale of the Apollo Program, the visiting president, and the helpful janitor serves as a memorable illustration of team engagement and an apocryphal narrative about storytelling. After all these years it still stands out as a great example of the motivating effect of an inspiring vision.

“We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organise and measure the best of our energies and skills.” John F Kennedy, 1962

Stories invite us to go on a journey and are so effective at delivering a message because they give the audience a way of engaging with the details and caring about the outcome. We are drawn in by being able to relate to the characters, their motivations and needs. We also recognise the challenge in the current state and become curious about how it can be resolved. The challenge may demand a journey or quest, which we hope will have a fitting outcome.

Every organisation has it’s own narrative and while not all projects and stories can be as uplifting or as clear-cut as a mission to the moon, seeing our place in a bigger picture can invest work with more significance and be emotionally compelling. Having the opportunity to reflect upon a narrative and make sense of our role within it allows us to consider new possibilities, inspire us to take on new responsibilities and conduct our daily work mindful of a long-term strategic vision.

Most of all it helps us take ownership of the challenge and consider what we can do differently to help overcome it. The scale and status of one’s role does not necessarily define the value of each contribution.

Even though we may have little influence in the grander scheme of things, by taking personal responsibility to manage the quality of our work we can maximise the positive effect we have. And if everyone has this same personal investment in the outcome of the story there’s no limit to what can be achieved.

Sharing stories- Learning self-disclosure and vulnerability builds team cohesion

julian burton

I’ve recently been thinking about how important self-disclosure is in building relationships, and how I can learn to make it more of a part of my personal development. What started me thinking about this was a recent inspiring story about how England’s football squad learnt self-disclosure to build the trust and cohesion in the team we saw this summer in Russia.

In a recent Guardian article about the England football team’s sports psychologist, Pippa Grange, has been credited with their relative success in the 2018 World Cup by, amongst other things, encouraging self-disclosure amongst team members. As part of their training before the tournament, they regularly sat together and shared some of their intimate experiences and feelings, particularly around their fears about failure. The point, Southgate has said, is to build trust, “making them closer, with a better understanding of each other”.

Yet it can often be confronting to take of the armour off and share feelings and experiences at work. A lack of trust can mean that it’s not safe enough to reveal personal truths such as fear of failure. When you create a safe space to share its possible to learn about each other’s experiences, and in the process change our stories about ourselves and each other. As with the England team’s example, self-disclosure fosters stronger bonds between team members, uniting them around a common task or purpose and so improving performance.

In our experience we find that the most meaningful and motivating narratives are co-created through sharing stories. When people have opportunities to share how they feel, what they value and what motivates them, the shared narrative that emerges builds a stronger sense of belonging and common purpose. It’s common in organisations these days for leaders to want to create a new strategic narrative. Developing a shared narrative helps groups make sense of change, linking personal experience and identity to the organisation purpose and its wider context.

In the 2014 World Cup, it was reported that some of the England players were actually questioning whether they wanted to play or not, such was their fear of failure. Compare that to 2018. When Fabian Delph’s wife was about to give birth, his team paid for a chartered jet to allow him to be there for it and get back in time to play Belgium.

This is a wonderful story about Pippa Grange’s vision and commitment for creating a new team narrative of belonging and cohesion, nurtured through taking risks and encouraging the self-disclosure that led to a more effective team that we can all be proud of.

The Goal is One Team

julian burton

Ivory Tower

Chris Hayes

The Picture in the Attic

julian burton

Every once in a while there is news of a trusted, successful brand that suddenly lurches into unexpected trouble. More than suffering from misfortune, they are revealed as deeply flawed, and are not what they seemed to be at all. When the internal reality doesn’t match the projected image they are effectively living a double life - one that is ultimately unsustainable.

Is it unreasonable for an organisation to want to project a flattering picture of itself, to instil pride and confidence in it’s staff and customers, while shying away from contemplating its faults and weaknesses, be they systemic or those of individuals?

Imagine if all the challenging, difficult stuff could manifest itself in a ghastly hidden picture instead of being lived, worked-out and resolved – like some fantastic deception in a gothic novel. That could be tempting, especially if problems are being suffered and managed by others and all the easier to disregard. Some may consider things are better left unsaid, to allow them to be managed discreetly and preserve the reputations (and dignity) of those involved.

However, exploring troubling issues openly can establish their true extent throughout the organisation, as well as offering a valuable opportunity to share experiences, correct misconceptions, and learn from each other.

While it may be appealing to avoid the upfront cost and disruption of directly confronting difficulties, how costly will it be in the long run to constantly bend to accommodate them? An informed, strategic response can attempt to share out the burden more fairly, rather than leave problems to be borne by just the individuals directly impacted. That could make for a story with a happier ending for everyone, not just those telling it.

Blame it on Blame Culture

julian burton

Why is it so hard to make change happen?

julian burton

Despite the efforts that leaders go to in communicating their future vision to their employees, many change initiatives still fail.

Leadership and employees need the opportunity to develop a shared, personal commitment to the change needed, and an understanding of how to deliver it.

What is the human cost of holding a "them" and "us" attitude about the people you work with?

Delta7 Change

One of the most pressing challenges that we experience when we work with organisations is the perjorative use of the pronoun “they”. It can creates internal silos and people “chucking things over the wall at each other” without understanding the impact of their actions or how they are unconsciously constructing stories about each other that get in the way of collaboration, and at what cost?

When you are focused each day on the challenges you and your team are facing it can firstly be overwhelming and secondly it can feel very isolating. More often than not we realise that issues have been built up and frustrations have evolved that are born of silence. When was the last time you discussed your relationship to another person at work? Probably never, right? It is still not the norm, not the done thing.

Yet what is the cost to the company of the existence of silos? In manufacturing, what is the cost of the rework it might mean? What is the cost of silos to your customer relationships? In the past collaboration, creativity and innovation have been things that organisations strived for to achieve a competitive advantage. Now it is becoming clear that they have become essential for survival.

So how do you break down these silos?

In the first instance – talk to each other. Make sense of the impact you each have and celebrate what works well.

In the second instance – contract with each other about how you will work together. Yes, it is counter to most organisational cultures to discuss such topics, but agreeing what you will do if something isn’t working for you and agreeing how you will talk about it, makes it far easier to bring up what could be seen as emotive topics.

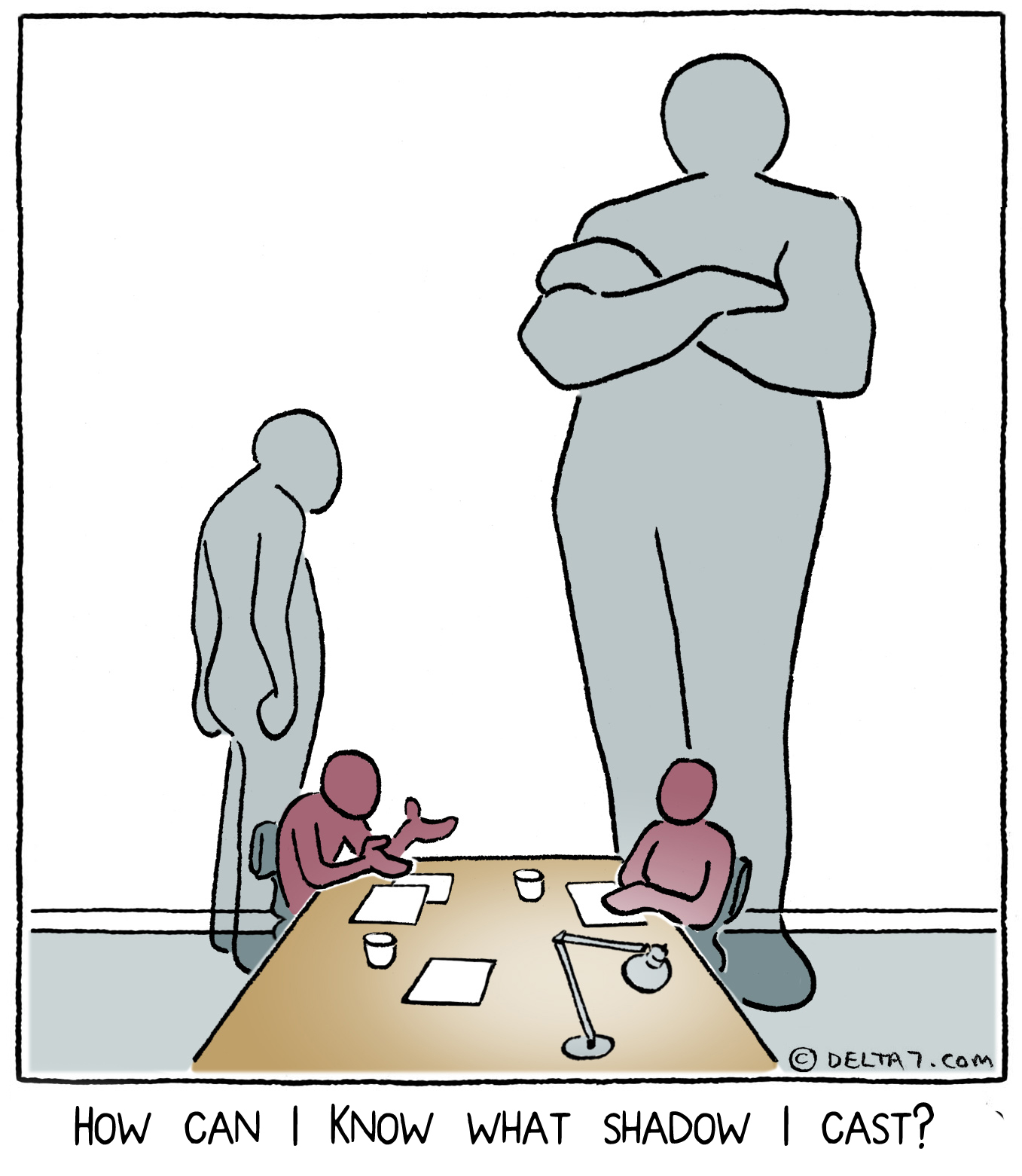

Me and my Shadow: How can I know what impact I have on other people in meetings?

julian burton

For me my shadow side is the parts of me I can’t see or I’m completely unconscious of that drive my behaviours and has a significant impact on the quality of my relationships. Have you been in a meeting recently and felt disempowered by someone who has dominated the conversation so much that there was no space for anyone else’s views? Or it felt too risky to share your thoughts, let alone give them feedback on their impact on you?

I’ve only learnt recently that sometimes my silence in a meeting can shut others down more often than my voice does! Since getting that gift of feedback I’ve become more sensitive to what happens in the interactions that I'm taking a part in. And I've become more curious about how I show up, and now want to learn more about the parts of my shadow that closes down others' voices and contributions.

Given that I can’t normally see my own behaviours, I really need others to give me honest feedback on what they see and the impact they have. The trouble is there can often be different realities existing simultaneously in a meeting; what I think I’m doing and how I like to think I’m showing up, and how others see me behaving. It can be obvious to other people how I’m behaving, yet hard or impossible for them to give me feedback if they don’t trust me or it doesn’t feel safe enough.

This is a real bind for me, as how can I learn to develop my self-awareness if it’s not safe enough for others to speak up and give me feedback on my behaviour? If I don’t know what impact I’m having I can’t learn to change my behaviours - to the ones that could create the relationships of trust needed for it to be safe enough for people to give me feedback in the first place! AARRGHH!

Moving on from my frustrations, I’ve been getting a sense that I need to work on learning to listen more deeply and actively, from a calmer place, responding differently from this position and noticing what happens. If the quality of trust shifts, I hope to get more feedback that can shine some light onto to the parts of my shadow that seem to close down others and get in the way of more open and honest conversations.